Background:

Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA)

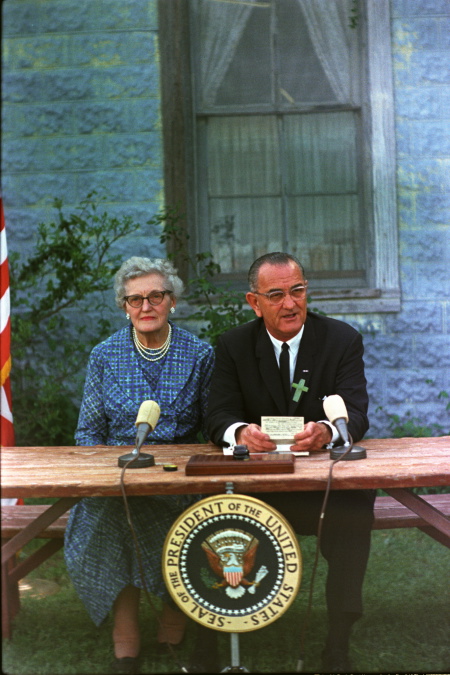

To understand No Child Left Behind (NCLB), it’s necessary to quickly review its history as a reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) signed into law in 1965 by President Lyndon B. Johnson. ESEA was a significant part of President Johnson’s War on Poverty initiatives because its goal was to close the academic gap between children living in poverty and children in the middle class.

While we now look at ESEA as an education statute, its roots are as a civil rights initiative. According to James Guthrie in his 1968 article on ESEA, its successful passage was partially due to the momentum caused by 1) the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision that found that racial segregation was unjust and 2) the 1964 Civil Rights Act’s law forbidding discrimination on the grounds of race, color, or national origin in any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.

Guthrie (1968) points out that ESEA passed in a controversial political environment, with Democrats largely voting for its passage and Southern Republicans voting against it. ESEA initially included six funding programs. Over time, its programs were revised, but the most significant program was Title I, which distributed funds to LEAs for children from low-income families. It remains the most powerful source of funding today. The ESEA controversy over equity and federal school funding continues to play out.

Learn more about education reform

The No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Reauthorization of ESEA

NCLB was the seventh reauthorization of ESEA. In 2002, President George W. Bush signed the act, making significant changes to previous reauthorizations as it sought to achieve equity through accountability to ensure that funding dollars were making a difference in every student’s academic progress. Scores on international standardized assessments indicated that the US was falling behind in global competitiveness and that the academic achievement of students of color, students with disabilities, and students from poverty continued to significantly lag.

Accountability: Proficiency for All

To ensure accountability, NCLB required that by 2014, all students must be proficient in reading and math. States were permitted to choose standards of proficiency and end-of-year assessments to evaluate proficiency, but the federal mandate stood. However, giving the states the power to define standards and assessments led to a large and perplexing range of defined proficiencies. In an Education Week article, David Hoff (2007) described an additional issue: “In a study comparing state test scores with NAEP results, the research group Policy Analysis for California Education found a widening gap between students rated as proficient on the national assessment and those at the same level on state tests.” It’s not difficult to see how the creation of Common Core standards entered the fray.

Annual Standardized Testing in Reading and Math

NCLB required that students in grades 3 through 8 take a standardized test in reading and math. High school students in grades 10-12 had to take at least one standardized test in reading and math. Additionally, schools had to disaggregate test results by subgroups such as students with disabilities, ethnic/racial minorities, children in poverty, and children whose first language was not English.

To support schools and districts with the federal mandate, Let’s Go Learn designed its two flagship adaptive diagnostic assessments. Its math diagnostic, ADAM (Adaptive, Diagnostic Assessment of Mathematics), and its ELA/reading diagnostic, DORA (Diagnostic Online Reading Assessment), went through rigorous research to ensure validity and reliability. Teachers and administrators were able to use the assessments to identify critical instructional areas and learning gaps as benchmarks for Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP).

Adequate Yearly Progress

To track student progress toward proficiency, NCLB required that schools make Annual Yearly Progress toward their proficiency goals. NCLB also mandated strict rules for Title I schools that did not make AYP two years in a row. Students attending these schools could transfer to other more successful schools in their districts. Schools that did not make AYP for three years in a row had to offer students free tutoring. The most serious sanction was that states could close schools that continually missed AYP, turn them into charters, or take them over.

As part of NCLB’s goal of ensuring that progress included all children, 2001-02 reading and math assessment data had to be used as a baseline, and benchmarks were set indicating how progress would be made toward universal proficiency in spring of 2014. Moreover, data had to be disaggregated for students on average and for impoverished students, students with disabilities, English language learners, and African-American, Asian-American, Caucasian, Hispanic, and Native American students. 95% of all students and students in subgroups had to make AYP.

Let’s Go Learn’s Research-Based Solution for Meeting AYP

Let’s Go Learn determined that it could support schools in ensuring that AYP was met by providing adaptive diagnostic assessments and supplementary learning programs designed to fill learning gaps and encourage effective teaching and learning. These two programs, LGL Math Edge and LGL ELA/Reading Edge, use ADAM and DORA data to analyze an individual student’s strengths and weaknesses. The learner’s profile generated by the diagnostic assessments is translated into a set of instructional objectives from which the LGL system creates Specially Designed Instruction based on student skills rather than on grade level. District teachers began to use the LGL Edge programs with the diagnostic assessments to support AYP.

Special Education

NCLB’s focus on progress for students in every disaggregated group contributed some bite to the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA), which provides services to students with disabilities. Prior to NCLB, students with disabilities were not often assessed in the same way as students in general education and didn’t have access to the same programmatic learning solutions. NCLB mandated that students with disabilities had to be assessed and that they could use accommodations when taking standardized tests. Further, their AYP had to be measured.

According to Wrightslaw in an article about the impact of NCLB on students with disabilities, “Since a large number of students with disabilities would have to fail for this failure to have an impact on the district’s AYP status and since a great many students with disabilities can succeed on standardized tests, a finding of ‘needs improvement’ achieves the primary goal of this law – it shines a light on those groups of students for whom the American dream of a quality public school education has not always been a reality” (NAPAS, 2004).

Let’s Go Learn’s 5-Step System for Teachers of Students with Disabilities

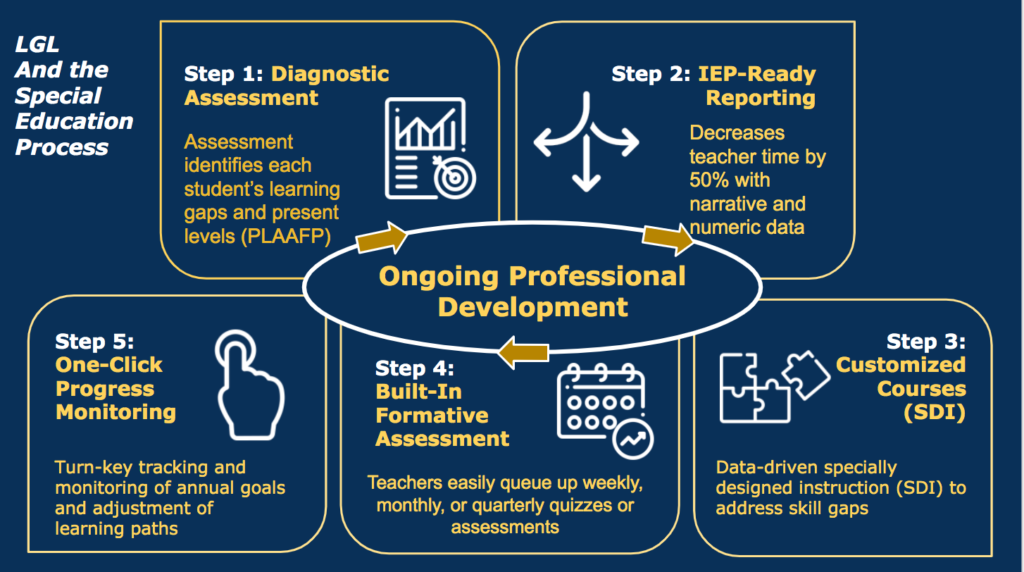

Early in its history, Let’s Go Learn recognized the importance of providing support to students with disabilities and their teachers and parents. The company developed a five-step process to clarify its research-based system.

Thousands of teachers have used LGL’s process to ensure student progress and legal compliance. These steps have been particularly helpful to novice special educators.

- LGL diagnostics analyze each child’s standards-based learning gaps and present levels (PLAAFP).

- IEP teams develop individualized education programs (IEPs) using LGL narratives and standards-based data.

- LGL system assigns specially designed instruction (SDI) for students with disabilities at the appropriate ZPD. Teachers can always self-select lesson assignments.

- LGL provides standards-based formative assessments that are vertically scaled into the original dataset.

- LGL provides ongoing progress monitoring, tracking student performance from the initial evaluation. No data collection is required by teachers.

Discover more about Let's Go Learn's data-driven assessments!

More info...Common Core Standards

When Common Core standards were published, many thought that these standards had been mandated by NCLB. However, the Common Core initiative was formed in 2009 not by the federal government but by governors and state commissioners to create a set of standards that each state could embrace. Between 2010 and 2011, 45 states and Washington, D.C. signed up to use the Standards, but political disagreements between conservatives and liberals soon eroded support for the initiative. Essentially, the struggle with Obamacare influenced attitudes toward Common Core, which some pundits called Obamacore, and the ongoing debate of where states’ powers begin and federal powers end fueled the end of Common Core as states begin to opt out.

Highly Qualified Teachers and Research-Based Instructional Programs

To ensure equity among schools and students, NCLB required every teacher to be “highly qualified,” including teachers of core content subjects, English language learners, and students with disabilities. To be considered highly qualified, teachers had to have a bachelor’s degree and demonstrate their expertise. However, states could decide how teachers demonstrated this expertise. The goal of the mandate was to ensure that students in every subgroup had highly qualified teachers. The hypothesis was tested by a study in 2007 by Rand, and the findings indicated “that high-poverty and high-minority schools had higher percentages of teachers who were not highly qualified under NCLB than low-poverty and low-minority schools. For example, teachers who were not highly qualified were three times more likely to be teaching in high-minority schools than in low-minority schools” (Berman et al., 2007).

Weighing the Outcomes of NCLB

NCLB’s goal of universal proficiency in reading and math was an attempt to transform a vision into a reality. Deven Carlson in his study of NCLB wrote that the law was doomed because it set a terminal goal of universal proficiency: “If they had left 100 percent proficiency as an aspiration rather than a mandated accountability target, it’s conceivable that NCLB could have survived politicians’ aspirational rhetoric and impossible promises” (Hess, 2021). NCLB did not significantly impact student achievement. The goal of all students reaching proficiency regardless of their starting point was simply impossible, causing sanctions to be levied and the involvement of the federal government to increase. Educators began to complain that the sanctions were forcing teachers to teach to the test. After 13 years, NCLB was replaced by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) Replaces NCLB, 2015

President Barack Obama signed the 8th reauthorization of ESEA on December 10, 2015.

The Every Student Succeeds Act shifted accountability back to the states, giving each one the right to choose “academic standards to adopt or develop that are aligned with college entrance requirements and relevant State career and technical education standards.” However, the new act continued with the requirement that students undergo yearly testing in grades 3 through 8 and once in high school. To measure AYP, states had to add at least one other measure to test scores to evaluate school effectiveness, and disaggregation of reporting continued as a mandate. But while states have to report test scores, there are no longer sanctions for not raising test scores, and student proficiency is no longer a federal requirement.

President Barack Obama signs S. 1177, Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), during a bill a signing ceremony in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building South Court Auditorium, Dec. 10, 2015.

ESSA Federal ESEA Title Programs

- Title I, A Programs and services for struggling learners

- Title I, C Migrant Education

- Title I, D Institutional Education

- Title I, G Advanced Placement

- Title II, A Teacher & Principal Quality

- Title III, English Learners & Immigrant Students – Language Instruction

- Title IV, A Student Support & Academic Enrichment

- Title IV, B 21st Century Community Learning Centers

- Title V, Rural Education Achievement Program

- Title VI, Indian, Native Hawaiian, Alaska Native Education

- Title IX, Homeless Education (McKinney-Vento Education for Homeless Children & Youth Program)

Resources

Birman, Carlson, et al. (2007). “Evaluating Teacher Quality Under No Child Left Behind.” Rand Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9287.html

ESEA Network. “About ESEA.” ESEA Network. https://www.eseanetwork.org/about/esea

Guthrie, J.W. (1968). “A Political Case History.” Phi Delta Kappan. https://kappanonline.org/political-case-history-passage-esea-guthrie/

Hess, R. (2021). What Next-Gen Accountability Can Learn from No Child Left Behind, Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/opinion-what-next-gen-accountability-can-learn-from-no-child-left-behind/2021/08

Hoff, D. (2007). “Not All Agree on Meaning of NCLB Proficiency.” Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/not-all-agree-on-meaning-of-nclb-proficiency/2007/04

Klein, A. (2015). “No Child Left Behind: An Overview.” Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/no-child-left-behind-an-overview/2015/04

NAPAS. (2004). “Children with Disabilities Under No Child Left Behind: Myths and Realities.” https://www.wrightslaw.com/nclb/info/myths.realities.napas.htm

Paul, C.A. “Elementary and Secondary Act of 1965.” VCU Social Welfare History Project. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/programs/education/elementary-and-secondary-education-act-of-1965/

Leave A Comment