Reading Intervention Program

Differentiated online reading curriculum for intervention, remediation, and enrichment

Online K-12 supplemental reading curriculum that targets each student’s learning gaps

LGL ELA Edge is a research-based supplemental reading program that begins with a diagnostic assessment of the performance of struggling readers. The program then provides individualized direct instruction and interactive learning activities to close learning gaps.

The LGL system captures all data and provides real-time narrative reports for progress monitoring. Reports at the classroom level break students into groups that share learning gaps in particular reading objectives. Formative and benchmark assessments allow educators and parents evidence of student mastery.

School districts across the nation use ELA Edge in elementary school, middle school, and high school to ensure that all students demonstrate proficiency in reading skills because there is an intricate connection between reading and academic and career success.

Core reading curriculum includes key components of reading: high-frequency words, phonemic awareness, phonics, oral reading fluency, spelling, vocabulary development, and reading comprehension strategies, as well as literary vocabulary and grammar lessons to support writing skills.

Lessons in LGL ELA Edge’s reading program have been carefully curated to help all students who need effective reading intervention programs, including students in Response to Intervention (RTI) programs, programs for students with disabilities, English Learners (ELs), and students with diverse learning styles. LGL ELA Edge is perfect for students who need help in building foundational skills, in reviewing grammar rules, or in developing deep reading skills.

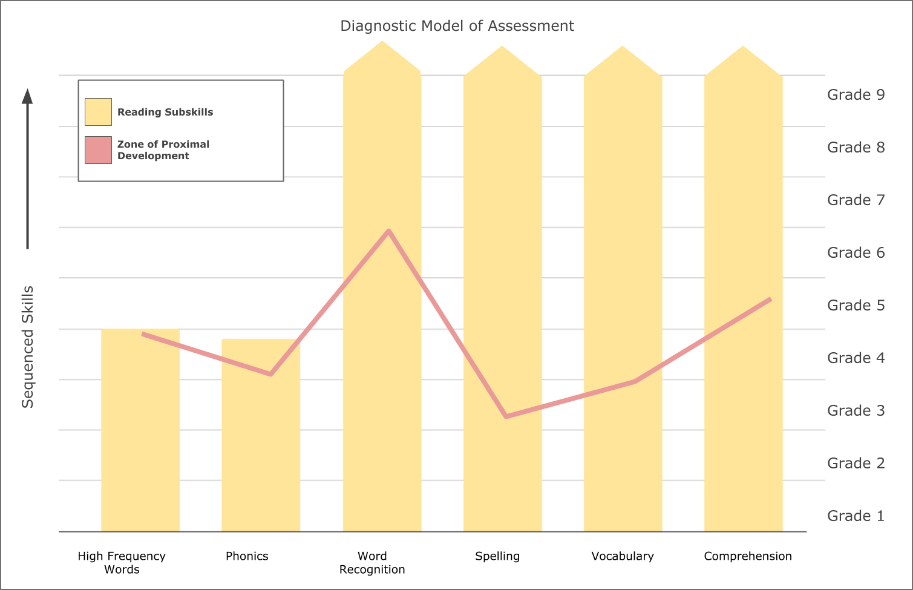

Our effective reading instruction begins with a granular diagnostic assessment.

Effective reading instruction for intervention and remediation begins with a granular diagnostic assessment that identifies student strengths and weaknesses.

LGL ELA Edge’s instructional solutions use our diagnostic assessments to identify reading/ELA learning standards that students have not yet mastered. Unlike summative assessments, our diagnostic assessments identify each student’s ZPD (zone of proximal development) prior to assigning instruction. This ensures each child or student is constantly working at the correct level rather than at an arbitrary grade-level placement.

LGL ELA Edge automatically assigns instruction for students that provides a personalized online learning path for each student in need of additional reading support or literacy intervention. Teachers can then use our formative assessments, such as our weekly quizzes or quarterly tests, to monitor student progress. Research clearly shows that comprehensive critical reading skills and research-based strategies lead to long-term student achievement. At the end of personalized learning paths are successful readers.

Our research-based instruction is designed to be equitable, effective, and engaging.

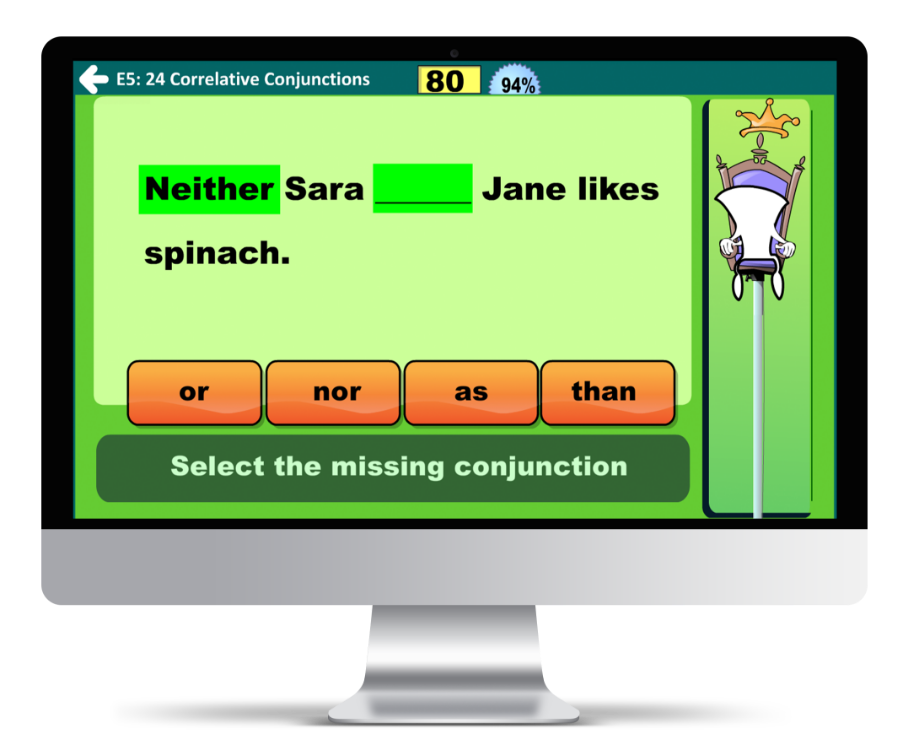

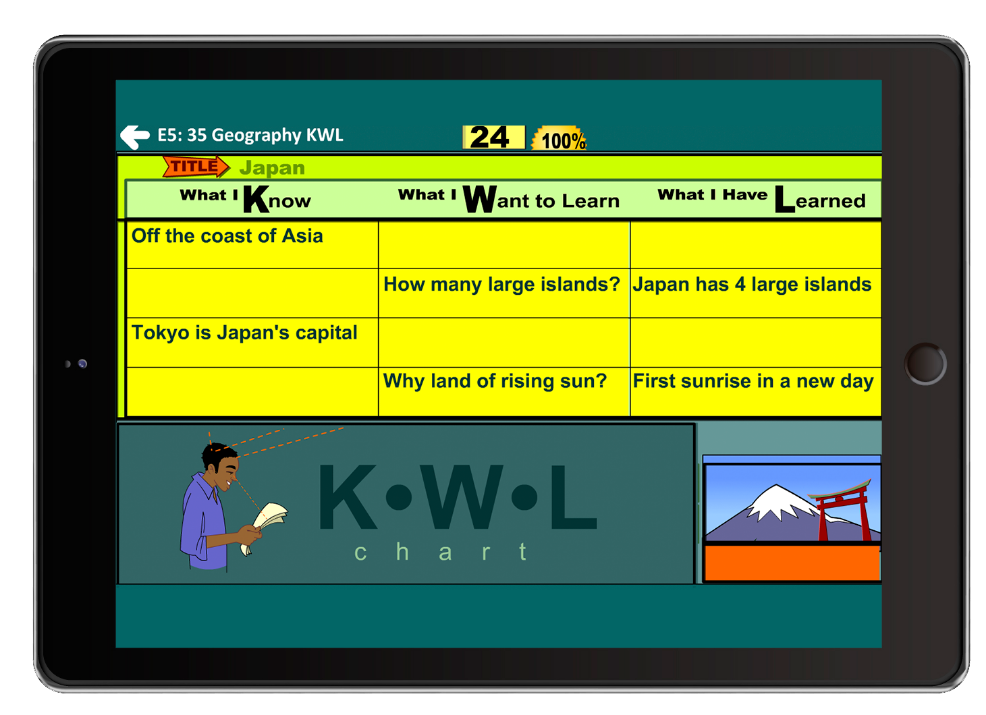

LGL ELA Edge uses the same instructional levels identified during our powerful assessments to generate an engaging, personalized course for each student. Every LGL ELA Edge lesson provides explicit instruction and practice that is in a student’s ZPD and cognitively accessible through animations, songs, graphics, and interactivity. Students are engaged with properly leveled content that reinforces newly mastered critical skills and concepts during gamified instructional practice.

Because practice activities are gamified, individuals are motivated to play until they reach optimum “scores” that act as progress indicators. Practices deepen conceptual understanding and critical thinking and can be used for independent practice, small group instruction, or extra practice for whole-class teaching. As students work through explicit instructional lessons specially designed to be at the perfect level, our responsive platform employs immediate corrective feedback. If an answer is incorrect, a learner learns why and can then continue to practice until mastery is reached.

Our data-driven supplemental reading instruction works for multiple reading initiatives.

As students work within LGL ELA Edge, all progress monitoring measures are captured and immediately available for educators to explore in easy-to-understand, actionable data reports. Teachers can analyze sharable reports for an individual student or for the whole class and use data and recommendations to plan teacher-directed whole-class curriculum or to target skill gaps for scaffolding intensive intervention. With access to rich, actionable data and supplemental instructional tools and materials, educators can easily progress monitor IEPs, determine benchmark goal attainment, and inform parents about student academic growth.

Every skilled and therefore confident reader is more likely to experience long-term benefits in educational and career pursuits. On the other hand, research shows that fourth-grade students who are not proficient readers will experience difficulty in content area education that relies on reading skills, strategies, and processes. LGL ELA Edge provides teachers with systematic personalized instruction driven by diagnostic and formative assessment.

LGL ELA Edge Key Features at-a-Glance

Common Questions

Will LGL ELA Edge support accelerated learning to make up for learning loss or unfinished learning due to the pandemic?

Will LGL ELA Edge fulfill the Texas HB4545 legislation requiring immediate intervention in the fall for any student with a non-proficient on the STAAR state test?

Does ELA Edge include grammar lessons?

Is LGL ELA Edge appropriate for K-3 reading?

If I have a Tier 1 student who has a learning gap in only a few areas of reading, can I use LGL ELA Edge for short-term intervention in RTI and MTSS?

What process did Let's Go Learn's curriculum developers use to create LGL ELA/Reading Edge?

Is LGL's Reading Edge aligned to the Science of Reading?

Reading intervention

The term reading intervention refers to programs designed to “intervene” when traditional reading programs don’t help students overcome reading difficulties. We know that the process of making meaning from text no matter the medium is critical to a student’s well being and academic achievement not just for elementary students and high school students but in college and career and throughout life. The good news is that most students can improve their reading ability with evidence-based programs that provide effective reading instruction and intervention.

Who needs reading intervention?

Identifying individual students who need evidence-based interventions requires that teachers can determine the difference between students in the early grades learning at different rates and students in all grades needing individualized instruction in different reading concepts, processes, strategies, and skills. Because each student learns in unique ways, it is not an easy task to match a particular intervention for an individual student. Note: This is why universal screening or granular diagnostic assessments are necessary to support teachers in identifying for each student the short term or long term support they need. “Deficits in phonological awareness, rapid naming, fluency, and the alphabetic principle appear to be the most consistent predictors of initial response to intervention (Al Otaiba & Fuchs, 2002; Lam & McMaster, 2014; Nelson et al., 2003)” (Wenzek, 2018).

History of reading intervention

In the last part of the 19th century, educators began to question why certain students seemed unable to learn how to read using traditional methods that worked with the majority of students. This began the journey — not yet over — to discover what causes reading difficulties and how to remedy them.

In the early 1920’s, Grace Fernald at the University of California, Los Angeles’ University Training School developed a reading intervention program with Helen Keller. Called the Fernald method, it focused on kinesthetic strategies wherein students learned words one at a time, tracing each cursive letter and then identifying the word in print and eventually combining words to create sentences, paragraphs, and passages. “Fernald and Keller presented three case studies in which non-readers achieved grade-level fluency and comprehension after four to six months of treatment” (Scammacca et al., 2016).

During the same basic timeframe as the Fernald method was popularized, W.S. Gray developed a method that was the precursor to the Response to Intervention (RTI). His approach was so individualized that he advised educators to use his case studies to determine methods that would help their students. “He did state that treatment included exercises to improve word and phrase recognition, story recall, and reading comprehension. Gray also emphasized the importance of choosing reading material that appealed to the student’s interests” (Scammacca et al., 2016).

Later in the 1920’s, Arthur Gates, an education psychologist, developed a reading intervention that focused on diagnosing reading issues and solutions for the individual student. Seeking to educate teachers and reading specialists, in 1928 he published the first of three editions of The Improvement of Reading: A Program of Diagnostic and Remedial Methods. His recommended strategies included word recognition, vocabulary acquisition, left-to-right eye tracking, and reading comprehension ((Scammacca et al., 2016).

In the late 1930’s and 1940’s, the focus of reading intervention approaches took a 180 degree turn from the theories of Gray and Gates. The burden of helping children with reading difficulties moved from the educator to the psychologist. Psychological disorders were perceived as causal. “Psychoanalytic viewpoints on reading disabilities prescribed psychotherapy as the preferred intervention, either before or in addition to more traditional reading interventions. They also recommended that parents create a home environment that resolves the child’s aggressive urges and/or anxiety” (Scammacca et al., 2016).

In 1955, this trajectory changed again with the publication of Why Johnny Can’t Read by Rudolf Flesch, who addressed his theories on the cause of reading difficulties to parents. Essentially he placed the blame squarely on schools and their failure to teach phonics as an integral part of teaching children to read. While his theories on the importance of phonics came under fire, he reiterated his premise in Why Johnny Still Can’t Read in 1981. His essential premise would rise again in the Science of Reading movement in the 2000s.

While Flesch continued to encourage parents and teachers to use phonics to teach reading, intervention strategies focused on areas: reading comprehension and metacognition.While approaches differed from district to district and state to state, the 1980s saw the pendulum swing with two new programs: Reading Recovery and Whole Language.

“Reading Recovery specifically, and whole-language reading instruction generally, spread like wildfire through the education world…” (Lemann, 1997). The Reading Recovery program was founded by Dr. Marie Clay in New Zealand.and was brought to the U.S. around 1984. The program is designed to help first graders struggling to learn to read with individualized instruction from Reading Recovery tutors. While it is still used in schools around the world, many U.S. educators criticize it for its lack of a scientific base. Dr. Joseph Torgesen dimmed the enthusiasm for this method, stating in an interview stated his opinion on Reading Recovery: “Independent analyses show that Reading Recovery does not accomplish the goal of preventing reading difficulties in young children as effectively as its own ‘in house’ research show, nor does has Reading Recovery responded to research that has identified its weaknesses” (Torgesen, Wrightslaw).

Around the same time that Reading Recovery was making its way into U.S. schools, the whole language approach was founded by Frank Smith and Kenneth Goodman They presented whole-language instruction as “a joyful, humanistic, intellectually challenging alternative to deadening phoneme drills — one that turns the classroom from a factory floor into a nurturing environment in which children naturally blossom” (Lemann, 1997). Whole language kicked off a sort of war between direct instruction and immersion (with the terms taking on political rather than educational meaning) and gradually the whole language movement evolved into a movement to balanced literacy.

In the 1990s, reading intervention focused on metacognitive and comprehension skills, with attention to such strategies as summarizing, cognitive mapping, and self-questioning. “Interventions that targeted building reading comprehension skills in struggling readers became almost a singular focus of researchers in the 1990s, with many more experimental studies devoted to comprehension skills. Larger effects were associated with studies that taught self-questioning strategies compared to those that enhanced the text or provided general reading comprehension skills instruction” (Scammacca et al., 2016).

In the 2000s, approaches ranged from multi-tiered approaches such as RTI and MTSS, Structured Literacy, Balanced Literacy, and then back to a similar approach to Flesch’s – the Science of Reading. “Studies have shown that explicit, systematic instruction in how letters represent sounds—phonics—is the most effective way to teach kids how to read words. Teaching students to rely on other clues, like pictures, takes their focus away from the letters. And restricting students to books deemed “at their level” can actually widen achievement gaps” (Schwartz, 2022). The battle among approaches continues to cause consternation and a desire to find a method or approach that will show evidence of reading achievement for most if not all students.

Reading instruction versus reading intervention

Reading programs often offer evidence-based reading instruction and evidence-based interventions. For students in kindergarten to grade 3, the path to literacy includes both reading instruction and reading intervention. Why? Children enter kindergarten with very diverse backgrounds that include the following: language spoken at home, language development, exposure to fiction and nonfiction stories, storytelling as a natural part of family experience, and alphabetics.

Because children begin the formal process of learning to read with diverse language backgrounds and reading experiences in English, teachers have the difficult job of assessing individual students to determine student needs. “Research shows that beginning readers need to master many skills in multiple domains to be proficient in reading. Three important reading domains are alphabetics, reading fluency, and reading comprehension.”

Reading instruction for all students should be composed of instruction in these essential components(IES – REL Midwest. What Works Clearinghouse Practice Guide).

- Alphabetics: “identify and manipulate units of oral language, identify letters, and apply an understanding of letter-sound relationships”

- Reading fluency: “read text accurately, automatically, and with expressions”

- Reading comprehension: “understand the meaning of text, including the ability to decode words, understand word meanings, and interpret language”

In addition to core reading programs for all children, teachers must distinguish between students on the path to literacy and students who need intervention before they can move smoothly along the path. For example, teachers may find that some children are dyslexic. The National Center for Learning Disabilities reports that approximately one out of every five children has been diagnosed with some form of dyslexia. Dyslexic individuals typically experience difficulty processing information presented visually, such as words printed on paper. They also tend to have trouble understanding spoken language.

Teachers also have to distinguish between the path to literacy for native English speakers, English Learners, and English Language Learners. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, about 50 million people in the United States speak a language other than English at home. Many of these children come from immigrant families where English is not the primary language. In addition, many schools in the United States serve large numbers of students whose native languages are not English. For example, nearly 40 percent of California students attend bilingual programs.

For students in elementary grades 4-9, What Works Clearinghouse recommends that instructors differentiate reading instruction for students to optimize student reading skills for complex vocabulary and text. The four components of reading to focus on include the following (IES, Providing Reading Interventions for Students in Grades 4-9):

- Decoding

- Fluency Building

- Making meaning

- Making sense of challenging texts

65% of America’s fourth graders do not read at a proficient level (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2010).

While many fourth graders are not proficient in reading, the good news is that most students can improve their reading ability. However, it takes work and effort. Research indicates that students who receive intensive, appropriate evidence-based interventions are much more likely to succeed in school. “Students in classrooms where evidence-based fundamentals of reading instruction are deliberately implemented are far less likely to demonstrate reading difficulties. Enhanced general education instruction in the early grades reduces the number of children who do not meet grade-level benchmarks and start to fall behind, and therefore it reduces eventual referrals to special education” (Vaughn & Fletcher, 2020).

Current trends

The response-to-intervention and multi-tiered approaches

Currently there are two popular tiered approaches to dealing with reading instruction and intervention and three programs that combine different elements of reading and writing practices. All require teacher professional development for effective implementation.

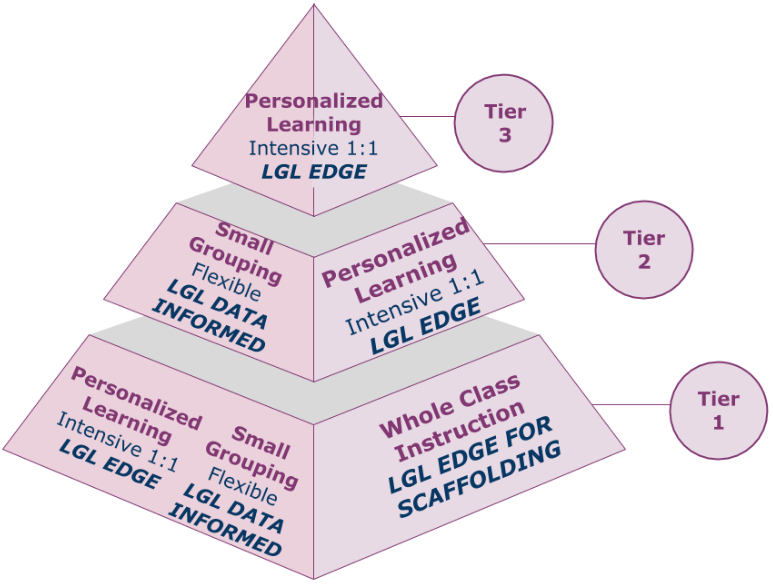

Two of the approaches use a paradigm that proposes a tiered approach. Each begins with a reading diagnostic assessment of each student.

- What is the Response to Intervention Approach?

- “Stated plainly, RtI results from the marriage of a long history of evidence-based practices (and the lessons learned there from) with a new and more efficient resource-deployment system (the Three-Tier Approach) that better allows schools to match instructional resources directly to the nature and intensity of student learning needs. Fancy sounding words that basically mean that RtI lets schools look at kids’ needs and use their resources most efficiently to provide effective instruction for all of them” (W. David Tilly, PhD, RTI Action Network).

- What is the MTSS Approach?

- “The importance of the multi-tiered approach (now cast as “multi-tiered systems of support:” MTSS) is evident in the evolving structure of response to intervention, the application of positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS), recent amendments to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESSA: 2015), and emerging elements of the reauthorization of Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)” (Swenson et al., Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services Blog).

The RTI and MTSS tiers are similar in their academic approach, but MTSS is more comprehensive and includes supports for behavior, social and emotional needs, and absenteeism.

The response-to-intervention and multi-tiered approaches

Tier 1: general education – Assumption is 80 to 85% of students will learn to read using research-based core curriculum.

Tier 2: early intervening services – Assumption is 10-15% will learn to read in small groups with additional time and focused evidence-based interventions.

Tier 3: Intensive intervention – Assumption is 5% of students will need intense, individualized instruction in focused areas. Some may be eligible for special education, in which case a special education teacher may use additional practices while closely monitoring and adjusting instruction.

What Works ClearingHouse recommends that Tier 3 students receive individualized evidence-based instruction in these principles (IRIS Center, Tier 3):

- Systematic instruction: lessons sequenced to build from simple to complex skills and concepts

- Explicit instruction: direct instruction on a single skill or concept that build on and is connected to prior learning

- Frequent review: ongoing review of learning critical components to ensure master over time

- Opportunities to practice: activities that practice skills or concepts to ensure mastery over time

- Scaffolding: evidence-based learning supports during initial instruction that scaffold new learning until mastery is independent.

To ensure equity, school personnel must consider the following when identifying students for Tier 3 services (IRIS Center, Cultural Diversity):

- Understand and respond to cultural differences

- Measure the student’s language proficiency

- Determine the cause of the student’s reading problem

- Administer non-biased assessments

Three contemporary approaches toreading

Structured Literacy

Structured literacy (SL) combines foundational skills (e.g., decoding, spelling) and higher-level literacy skills (e.g., reading comprehension, written expression). It also includes phonemic awareness, oral language sensitivity, and sound manipulation. “Research over the past couple of decades has suggested that, although any phonics is better than no phonics at all, certain types of phonics approaches are more effective than others. Specifically, an initial phoneme-grapheme level approach—that is characteristic of structured literacy—is more effective than a larger-unit phonics approach such as onset-rime, analytic phonics, or word families” (Spear-Swerling, 2019).

Balanced Literacy

Balanced Literacy combines teaching reading and writing using authentic literature and the writing practice as well as direct instruction and core phonics skills instruction. As with most evidence-based programs, necessary elements include individualization for each student, teacher training, and instructional differentiation. “A balanced literacy framework uses specific instructional routines such as guided reading, shared reading, interactive writing, literacy centers, and independent reading and writing (Fountas & Pinnell, 1996, 2001)” (John, 2016).

Science of Reading

In Kirstina Ordetx’s article on the Science of Reading, she cites a quote from David Kilpatrick, professor of psychology for the State University of New York College at Cortland, that clearly describes how teachers and parents perceive the model: “We teach reading in different ways; they [students] learn to read proficiently in only one way’” (Ordetx, 2021). Basically, the method defines three skills as critical to reading development: letters and sounds; phonic decoding, and orthographic mapping. The goal of this foundation is reading comprehension, which includes decoding of text and comprehension of language. Ordetx supplies Scarborough’s Reading Rope illustration to offer more specificity.

Let’s Go Learn’s online reading/intervention program

Let’s Go Learn began in 2000 as an effort to bring an academic reading model to the digital age. With the World Wide Web reaching mass market in the late 1990s, Dr. Richard McCallum of UC Berkeley took his reading and literacy development program and partnered with entrepreneur Richard Capone to create a web version of McCallum’s diagnostic assessments. Prior to this effort, McCallum’s program was a paper and pencil exercise, which had to be scored and interpreted manually. In 2000, McCallum and Capone began Let’s Go Learn with an initial vision to determine why students struggled in reading and how to better inform teachers on how to support student learning.

Shortly after its inception, Let’s Go Learn received a grant from the US Department of Education to compare its stand-alone reading assessment system with one-on-one assessments offered by highly-trained specialists in the CalReads program.This study provided statistical proof that Let’s Go Learn’s online assessments do indeed work as designed: automating the assessment process and producing expert-level reading profiles in a scalable manner that leads to effective data-driven instruction.

School districts experiencing success for the first time with struggling students asked LGL to develop parallel diagnostics in mathematics. Before long, requests for instruction that perfectly aligned with diagnostic data drove the development of personalized learning paths, SDI-developed lessons and an AI system that integrated the diagnostics with the learning paths and created a real-time tracking and reporting and progress monitoring system.

Today, Let’s Go Learn continues its data-driven, research-based approach to discovering how every student can master reading and math standards. Districts experiencing success for the first time with struggling students asked LGL to develop parallel diagnostics in mathematics. Before long, requests for instruction that perfectly aligned with diagnostic data drove the development of personalized learning paths, SDI-developed lessons and an AI system that integrated the diagnostics with the learning paths and created a real-time tracking and reporting and progress monitoring system.

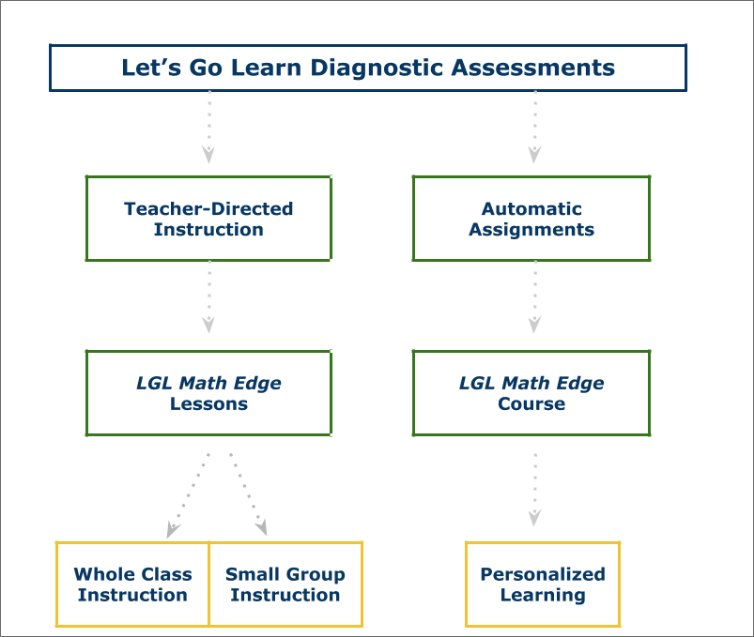

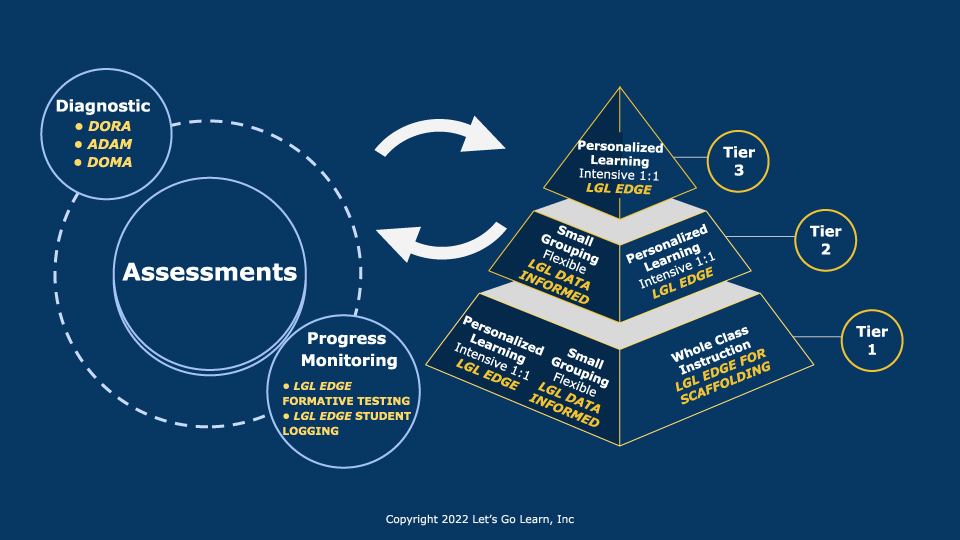

Overview of Let’s Go Learn’s reading intervention process

The Let’s Go Learn (LGL) process includes diagnostic assessments, individualized instruction and evidence-based interventions using Specially Designed Instruction and real-time tracking and progress monitoring. The LGL process simultaneously assesses, analyzes, and reports on multiple foundational reading skills and complex concepts and processes, while adapting to each learner’s individual ability in real time. After a student completes an assessment, the LGL platform automatically creates individual and class profiles, tiered grouping, standards reports, and classroom, school, and district progress and gains reports. It automatically analyzes student data and assigns courses and lessons that provide instruction and/or intervention until literacy achievement is optimal.

Personalized Learning: Operationalized for MTSS/RTI Sites

- First, students are assessed with the Diagnostic Online Reading Assessment (DORA). DORA is adaptive and thus can be used to assess all students quickly and efficiently. In cases where only a dyslexia screener is required and time is of the essence, DORA DS can be used.

- Students are efficiently placed into small groups as appropriate.

- For small groups, DORA data provides prescriptive information for small-group instruction, similar to how a reading specialist would assess each student.

- For students using our ELA Edge instruction, lessons can be assigned for scaffolding before core lessons.

- All students receive a unique learning path in the form of a custom-made course. Lessons include exactly what students need, building on what they have already mastered. These lessons include sight words, phonics, phonemic awareness, grammar, spelling, vocabulary, and comprehension strategies. In mathematics they include the five major strands of mathematics.

- The LGL ELA Edge lessons are automatically assigned using diagnostic and formative data. LGL Edge courses provide specially designed instruction that targets the gaps of each student.

- Progress monitoring comes in the form of either weekly or monthly follow-up testing. DORA can be broken up into any of these 7 individual sub-tests:

-

- Phonemic Awareness

- Phonics

- High-Frequency Words

- Word Recognition

- Vocabulary

- Spelling

- Comprehension

DORA Dyslexia Screener (DS)

DORA DS is a multiple-measured criterion-referenced assessment based on scope-and-sequenced sets of items organized by skill or concept. Many high-stakes tests or short-screener assessments use IRT (Item response theory) to come up with predictive scaled scores. This is helpful when someone is trying to use a subset of items to predict how students will do. The problem with IRT is that it works on the assumption that data from the many can be reflected on an individual. In the case of at-risk students, students with IEPs, this use of data is less accurate. These students are not the norm and thus a diagnostic approach must be taken.

DORA DS is defined based on what has become the industry standard for dyslexia screening which is to look at an expanded decoding set of abilities as show below:

- High-frequency words

- Letter identification

- Letter-sounds phonics skills and above

- Phonemic Awareness

- Rapid naming

Within each of these areas, a set of items is created on which all students are tested. Mastery is defined as 70-80% answering of the items in the set correctly. Students are given for instance 10 letters to identify. They are asked to click on the letter B. 9 choices are displayed in a random 3 x 3 grid layout. The 10 letters were chosen based on p-values ranging from 25% to 75%. When a student gets 70-80% correct, they are given a mastery on that particular set.

Depending on the sub-test, the student might then move on to a higher skilled set of items. In the case of phonics, the test moves from beginning sounds, to short vowels, to beginning consonants. This is the acceptable order in which phonics skills are taught.

As a result, each student is tested linearly upward to find their ceiling skill within the sub-tests listed above (1 to 5). This criterion-referenced method procedures scoring based on a fixed set of skills that are associated with each instructional grade-level from K to 2. So scores across multiple forms are always going to be the same since they are pegged against the same criterion-referenced set of skills and concepts. See next section for more expansion of how forms are created.

Dyslexia screening is based on industry best-practices of screening basic emergent literacy decoding skills. Dyslexia can only be diagnosed by a credentialed professional. Therefore to clarify, we provided a scaled raw score of 0 to 23 on decoding that can be interpreted as the risk of dyslexia. See the table that follows:

| Raw Score | GLS |

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0.06 |

| 2 | 0.13 |

| 3 | 0.19 |

| 4 | 0.26 |

| 5 | 0.33 |

| 6 | 0.39 |

| 7 | 0.46 |

| 8 | 0.53 |

| 9 | .059 |

| 10 | 0.66 |

| 11 | 0.73 |

| 12 | 0.79 |

| 13 | 0.86 |

| 14 | 0.93 |

| 15 | 1.1 |

| 16 | 1.2 |

| 17 | 1.3 |

| 18 | 1.4 |

| 19 | 1.5 |

| 20 | 1.6 |

| 21 | 1.7 |

| 22 | 1.8 |

| 23 | 1.9 |

We use a simple criterion-referenced model of moving students up the scope and sequence of the following 5 measures that defined dyslexia screening testing.

- High-frequency words

- Letter identification

- Letter-sounds phonics skills and above

- Phonemic Awareness

- Rapid naming

Objectively, the number of skills mastered is totalled across these five areas and this results in a raw score of 0 to 23. But teachers can view the break out of each score as well since a single scale may not be sufficient to understand biases. For example if a first grader is brand new to English reading but has oral language skills, one might see low scores in High-frequency words, letter identification, and phonics. But phonemic awareness and rapid naming may be on-grade. Overall, the student would be “at-risk” for dyslexia but up a deeper dive and consideration of the student’s specific background, the student may NOT be at risk.

DORA’s online diagnostic reading assessments

The design of Let’s Go Learn’s online diagnostic assessments, reporting, and AI system allow our team to accommodate the needs of school districts and individual schools, preserving all the while the validity and reliability of the assessments. Accommodations may include those for students with disabilities or other student impediments to testing. Our professional development and training include updating to include accommodations and strategies necessary for any changes made.

DORA (Diagnostic Online Reading Assessment) is criterion-referenced, adaptive in nature, and delivered online. It is diagnostic in nature and can be used as a measure of student growth. Post assessment, comprehensive reports are provided to teachers and administrators to help with SLO creations and monitoring. DORA diagnostically evaluates each student’s reading abilities while providing the highest level of reliability and accuracy with highly reliable assessments with overall high coefficient alphas.

In addition, test-retest consistency is high from 0.69 to 0.84. Sections that make up individual subtests are items written to test specific skills within the scope and sequence of the sub-test. These CBM level sections acquire their reliability in part from the test design that aggregates specific skills items together while maintaining p-values that range from 0.25 to 0.75. Individual field testing of each CBM level section requires a mastery versus non- mastery score of 0.75 or higher which was the lowest threshold requirement for decision consistency by pools of students with previously established skills mastered.

DORA was created to paint a picture of an individual’s reading strategies more accurately across multiple measures which follow a constructivist perspective of the reading pro (Flores et al., 1991). The most effective way to characterize a child’s reading ability is to assess his or her reading skills across a set of criterion-referenced categories that are important to the reading process. The eight reading skills measured by Let’s Go Learn are: 1) High Frequency Words, 2) Phonemic Awareness, 3) Phonics, 4) Word Recognition, 5) Vocabulary, 6) Spelling, 7) Silent Reading Comprehension, and 8) Fluency.

High Frequency Words Subtest

This subtest assesses children’s ability to automatically recognize words that have been identified as frequently occurring in books, newspapers, and other texts. This subtest uses words from Edward B. Fry’s 300 sight words as test items which have been broken down into three general levels of difficulty (Fry, Kress, & Fountoukidis, 2004). A child’s response time in identifying these sight words is recorded and factored into the scoring of the child’s performance on the assessment.

Phonemic Awareness Subtest

According to Ruddell (1998), by the time children are between three and four years old, they have learned most of the approximately 40 phonemes (discrete sounds in words) which comprise the English language. The ability to hear and manipulate these discrete sounds in spoken words is referred to as “phonemic awareness.” Children demonstrate their phonemic awareness by segmenting words into individual sounds (i.e., /fish/ into /f/-/i/-/sh/), deleting sounds in words, blending sounds, adding sounds, or substituting sounds within a word to make a new word. Some researchers have indicated that phonemic awareness is one of the best predictors of reading success (Stanovich, 1993-1994). Others further argue that phonemic awareness is both the prerequisite and consequence of learning to read (Yopp, 1992). As such, it is especially important to determine children’s level of phonemic awareness in the primary grades to ensure that they get any necessary intervention as early readers, lest they struggle with reading as young adults. Specific phonemic awareness categories tested include: 1) addition, 2) deletion, 3) substitution, 4) identification, 5) categorization, 6) blending, 7) segmenting, 8) isolation, and 9) rhyming.

Phonics Subtest

In addition to having an awareness of the discrete sounds in words, children need to master how sounds and words are represented in English. This is important because children need to be able to effortlessly decode and recognize familiar and unfamiliar words to help facilitate the process of negotiating the meaning behind the text (Adams, 1990; Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998). The phonics subtest assesses a child’s ability to recognize basic English phonetic principles of high utility (Pressley & Woloshyn, 1995). These phonetic principles include: 1) beginning sounds, 2) short vowel sounds, 3) blends, 4) the silent E rule, 5) consonant digraphs, 6) vowel digraphs, 7) r-controlled vowels, 8) diphthongs, and 9) syllabification.

Word Recognition Subtest

As in many informal reading inventories such as the Qualitative Reading Inventory (Leslie & Caldwell, 1994), the Basic Reading Inventory (Johns, 2001) and the Diagnostic Assessment of Reading (Roswell & Chall, 1992), DORA’s Word Recognition subtest assesses a learner’s ability to recognize leveled lists of words. In this subtest, children are presented with a number of increasingly difficult words until they reach a level at which they “frustrate” or stop recognizing the words presented to them. The final outcome of the assessment gives teachers an idea of the grade-level ability of a child to recognize words out of context. This assessment is important in identifying how well an individual can use what he or she knows about text to recognize words outside the context of a sentence and of increasing difficulty.

Vocabulary Subtest

A learner’s knowledge of words and what they mean is an important part of the reading process, as knowledge of word meanings affects the extent to which the learner comprehends what he or she reads (National Reading Panel, 2000). The vocabulary subtest assesses a child’s understanding of words. The words from this subtest were selected by teachers and reading specialists to reflect the types of words children learn in various disciplines at different grade levels and in various stages of their lives. Similar to the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (Dunn, 1959), in the vocabulary subtest children are asked to select the picture which correctly corresponds to a word they hear. The program continues to present children with increasingly difficult words until they make a certain number of errors. This subtest provides information about a child’s level of oral vocabulary.

Spelling Subtest

The process of spelling involves many cognitive processes. While each person uses different strategies for spelling words, these strategies usually have in common a familiarity with a particular word (i.e., familiarity with its meaning and visual exposure to the word), letter-sound matching, and confirmation of how the word “looks” (Bear et al., 2000; Ruddell, 1999; Gillet & Temple, 1994). Because spelling is also a generative process (as opposed to a decoding and meaning-making process in reading), it is natural for young readers’ spelling abilities to lag a few months behind their reading abilities. DORA’s Spelling subtest tries to capture the nuances of the different processes that children use to spell words by employing target words with increasing difficulty in different domains. In the process of creating the items for the DORA Spelling subtest, reading specialists created a list of recommended target spelling words by examining words commonly encountered in or taught at specific grade levels. The program stops administering words when a child consistently spells words incorrectly. Items from this subtest were chosen by reading specialists and classroom teachers to approximate the kinds of words children of a particular age would see in their classroom instruction.

Silent Reading Comprehension Subtest

The silent reading comprehension subtest forms the crux of DORA, which attempts to provide a window into the semantic domain of a learner’s reading abilities. The content of each silent reading passage is expository and written to reflect the subject areas that students of a particular grade level would encounter. In a variation on protocols for some informal reading inventories (Gillet & Temple, 1994; Leslie & Caldwell, 1994), children silently read passages of increasing difficulty and answer questions about each passage immediately after they read it. The questions for each passage are broken up into three factual questions, two inferential questions, and one contextual vocabulary question. The program stops administering passages and questions once a student misses a certain number of questions on a passage. It provides teachers with information about a child’s comprehension level.

Fluency Subtest

Fluency is included as a teacher-administered measure. In this subtest, children read aloud short-leveled passages with increasing syntactic complexity. Teachers time children’s reading of these passages and record their errors and prosody from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) Oral Reading Fluency Scale (1995).

LGL’s ELA/Reading Edge personalized curriculum

The LGL ELA/Reading Edge reading program analyzes the completed reading diagnostic assessment to identify patterns of strength and weakness in the student’s reading skills. The learner’s profile generated from the diagnostic assessment is then translated into an initial set of instructional objectives unique to that student. Driven by these adaptive diagnostic assessments, LGL ELA/Reading Edge provides individualized learning paths based on student skills rather than on grade level. Implementation requires that teachers have students take the diagnostics three times a year so that differentiated instruction is ongoing throughout the year.

LGL ELA/Reading Edge and cognitive load theory

In cognitive psychology, cognitive load theory was developed out of the study of problem solving by John Sweller (1988). This research supports the theory that when cognitive load is reduced by instructional design, learning will increase in effectiveness. Thus, it is good practice for instructional designers to incorporate the three types of cognitive load theory into their program design. LGL Edge’s design integrates all three of these types of cognitive load.

Intrinsic: Initially, all students complete the full diagnostic DORA assessment, which breaks the teaching of reading into seven sub-tests. This means that LGL Edge uses the identification of these multiple instructional points as the basis for how lessons are assigned and delivered to each student. Thus, the intrinsic cognitive load is reduced by not presenting topics or skills that are too hard or complex for a student to learn.

Extraneous: This type of cognitive load refers to the observation that some learning is more easily achieved with certain teaching methods. For instance, it is usually more effective to teach a learner the concept of a triangle by showing him or her a picture of a triangle rather than by trying to describe it in words. In the case of LGL Edge, lessons use music, graphics, and audio to present each lesson. These factors reduce the extraneous cognitive load significantly for each learner by presenting and teaching skills in a format that is easier for students to process and absorb. In addition, the gaming-interface design of LGL Edge allows students to learn more easily while earning points in a motivating game. This is a design that resonates with today’s students, who enjoy computer-based games and entertainment.

Germane: LGL Edge was designed with long-term retention in mind, which is the focus of germane cognitive load theory. Students are required to demonstrate the highest level of mastery by repeating lessons until they get to the Gold level or to 95% accuracy. Students are not allowed to repeat a lesson until two days after their first time completing it. These factors support the deeper learning of students across the LGL Edge content areas of reading and mathematics.

Content validity

The validity of an instructional program refers to its ability to support valid instructional inferences. That is, when implementation is followed according to best practices, do results support a valid conclusion about student learning? Building a valid program begins with accurate definitions of the content (i.e., the knowledge domains and skills). If the instructional activities correlate to the constructs that the program is designed to teach, then the program has content validity. Content validity is the basic logical bedrock of any instructional program.

The content validity of LGL Edge programs is driven by the valid and reliable diagnostic assessment data that organize instructional content. The content validity of Let’s Go Learn’s LGL Edge programs derives from the most current research-based and classroom-proven models of math and reading sub-skill acquisition. The reading models are based on the work of Richard McCallum, Ph.D., co-founder of Let’s Go Learn and the company’s Chief Educational Architect. Dr. McCallum combines superb scholarly and academic credentials with many years of practical experience in implementing extremely effective classroom instructional interventions. He is uniquely suited to guide Let’s Go Learn’s pioneering efforts in creating and expanding an online educational environment based on valid assessment and effective instruction.

Let’s Go Learn’s math programs’ content validity derives from best practices in math education. The development of these cutting-edge math products has been spearheaded by math specialist and teacher trainer Paul Giganti of UC Berkeley and Cal State Hayward. Prior to his work in professional development, Paul Giganti taught math in public schools for over 15 years. He has directed federally funded professional development programs in California under the auspices of the California

Post-Secondary Educational Commission. Currently he is the coordinator of the California Mathematics Council Festival Programs and Professional Development. In addition to his classroom teaching and professional development career, Paul Giganti has published several children’s picture books about mathematics.

Reliability

According to Allen & Yen (1979), reliability can be defined as the consistency between the observed use of an instructional program and the true effect at the end of instruction. While reliability is driven to a large extent by the features that are described earlier in this report, it is also dependent on using the implementation model designed to produce reliable results.

To ensure optimal progress, Let’s Go Learn recommends the following implementation model to support personalized learning:

- The teacher assigns students our online diagnostic reading assessment.

- Students take the online reading assessment.

- The assessment system adapts to each student, presenting more difficult or less difficult items based on student responses.

- The assessment system evaluates the student.

- The assessment system automatically populates teacher, administrator, and parent reports based on student performance.

- The assessment system assigns each student a course and targeted lessons within the course based on learning gaps.

- The teacher reviews LGL system assignments and accepts or overrides them.

- Students log in to their individual accounts 3-5 hours per week and complete lessons, earning points and certificates as they go.

- Teacher reviews instructional reports, which include scores, times repeated, time on task, initial score, and end score.

- Mid-year, the teacher assigns students one of our diagnostic

- This process continues, measuring student progress and updating each student’s lesson path.

- When the plan is implemented as described, educators can expect the instructional activities to support student progress to proficiency.

LGL progress monitoring

Progress monitoring comes in the form of either weekly or monthly follow-up testing. DORA can be broken up into any of these 7 individual sub-tests:

- High-Frequency Words

- Word Recognition

- Phonics

- Phonemic Awareness

- Vocabulary

- Spelling

- Comprehension

In addition, quizzes can be given that break skills down even further. If a tutor works on short vowels and wants to know if the student has mastered this skill, a quiz can be assigned remotely or in-class to the student. The final amazing piece is that all the information flows into the same vertically aligned data set. This means that progress monitoring is automatic and real-time. Teachers can administer the full DORA, individual sub-tests, or quizzes. All data flows into the same vertically aligned data set and can be graphed as shown above.

Essentially, once an assessment and progress monitoring articulation plan have been determined for tutors with remote and in-class students, progress monitoring is automatic. Finally, in terms of support, Let’s Go Learn is based on an Assessment-Instruction model. We will use this in our teacher training to help them use our data to determine why a student is struggling in reading and how to support the student as they achieve mastery.

The long term benefits of evidence-based reading/intervention programs

Let’s Go Learn has since its inception been dedicated to universal literacy. Literacy directly impacts well-being. Reading programs such as Let’s Go Learn’s reading/intervention platform support national and global literacy. Research finds that early identification and intervention can lead to improved outcomes for students who struggle with reading. Moreover literacy significantly impacts the future of children, families, and communities.

General education teachers play a critical role in identifying students who need assistance with reading and providing instruction to improve student achievement. ELL students, English language learners, students with disabilities, students of color, and students with low socioeconomic status often do not receive adequate support during the school day. This lack of attention contributes to the fact that over 30 percent of poor readers fail to meet state standards by third grade.

A number of factors contribute to a child’s ability to develop effective reading skills. These include family background, social environment, and access to quality early childhood care and education. However, research has shown that the most important factor influencing whether a child develops strong foundational reading skills is the amount of time spent engaged in reading activities across all media and content areas.

How does illiteracy impact society? Its reach is unfathomable.

- Good health versus shorter life expectancy

- Employment versus public financial assistance

- Active citizenry versus imprisonment

- High school and college graduation versus dropping out prior to high school graduation

- Self esteem and living wages versus generational cycles of poverty

“Low literacy impacts every aspect of life and every person as a result. Populations at-risk for unemployment, low educational attainment, and lack of access to healthcare overlap with areas where low literacy rates are highest. Unmet literacy needs create barriers to success, making access in such communities even more vital” (Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy).

Resources

Alsuwat, S. & Young J.R. (2016). Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Traditional versus Technology-based Instruction on Reading Comprehension of EFL Students. EFL Journal. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311104767_Meta-Analysis_of_the_Effects_of_Traditional_versus_Technology-based_Instruction_on_Reading_Comprehension_of_EFL_Students

Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy. The Reality of Literacy in America. https://www.barbarabush.org/why-literacy/

Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2010). Early Warning! Why reading by the end of third grade matters. https://www.aecf.org/resources/early-warning-why-reading-by-the-end-of-third-grade-matters

Current Evidence on the Effects of Intensive Early Reading InterventionsHernandez, Donald J. (2011) Double Jeopardy: How Third-Grade Reading Skills and Poverty Influence High School Graduation. Annie E. Casey Foundation. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED518818

Dickman, G.E. (2006). RTI and Reading: Response to Intervention in a Nutshell. Perspectives on Language and Literacy, Special Conference Edition. International Dyslexia Association: Baltimore, MD.

Institute of Education Sciences – REL Midwest. On course for reading success: Best practices for teaching beginning readers. What Works Clearinghouse Practice Guide. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/regions/midwest/pdf/infographics/teaching-beginning-readers-508.pdf

Institute of Education Sciences – What Works Clearinghouse. Providing Reading Intervention for Students in Grades 4-9. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/PracticeGuide/29

IRIS Center. Cultural Diversity. https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/rti05/cresource/q3/p08/#content

IRIS Center. RTI. https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/rti01/#content

IRIS Center. Tier 3. https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/rti05/cresource/2/p05/#content

IRIS Center. Characteristics of the RTI Approach. https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/rti05/cresource/q1/p02/#content

John, Tracy, L. (2016). Balanced Literacy in an Elementary Classroom. St Cloud State University. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1011&context=ed_etds

Nicholas Lemann. (1997) The Reading Wars. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1997/11/the-reading-wars/376990/

NCES. (2020). Reading Performance. Chapter 1, in The Condition of Education 2020. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/pdf/coe_cnb.pdf

Ordetx, Kirstina. (2021). What is the Science of Reading? The Journal of Multi-Sensory Education. https://journal.imse.com/what-is-the-science-of-reading/

Scammacca NK, Roberts GJ, Cho E, Williams KJ, Roberts G, Vaughn SR, Carroll M. A Century of Progress: Reading Interventions for Students in Grades 4-12, 1914-2014. Rev Educ Res. 2016 Sep;86(3):756-800. doi: 10.3102/0034654316652942. Epub 2016 Jul 9. PMID: 28529386; PMCID: PMC5436613.

Schwartz, Sarah. (2022) Why Putting the ‘Science of Reading’ into practice is so challenging. EdWeek. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/why-putting-the-science-of-reading-into-practice-is-so-challenging/2022/07

Squires K. E., S. Gillam, & D. R. Reutzel. (2013). Characteristics of Children Who Struggle with Reading: Teachers and Speech-Language Pathologists Collaborate to Support Young Learners. Early Childhood Education Journal. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257557025_Characteristics_of_Children_Who_Struggle_with_Reading_Teachers_and_Speech-Language_Pathologists_Collaborate_to_Support_Young_Learners

David Tilly, PhD. Who Founded RTI. RTI Action Network. http://www.rtinetwork.org/essential/255-who-founded-rti?tmpl=component

Joseph Torgesen. Reading Recovery for First Grade Children with Reading Difficulties. Wrightslaw. https://www.wrightslaw.com/info/read.rr.torgesen.htm

Sharon Vaughn & Jack M. Fletcher. 2021-22. Identifying and Teaching Students with Significant Reading Problems. American Educator. https://www.aft.org/ae/winter2020-2021/vaughn_fletcher

Louise Spear-Swerling (2019). Here’s Why Schools Should Use Structured Literacy. International Dyslexia Association. https://dyslexiaida.org/heres-why-schools-should-use-structured-literacy/#:~:text=What%20Is%20Structured%20Literacy%3F,reading%20comprehension%2C%20written%20expression).

Swenson, R. Bradley, R. Horner, & C. Calkins. In Recognition of Hill Walker’s Contributions to Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS). Office of Education and Rehabilitative Services Blog. https://sites.ed.gov/osers/tag/mtss/

Wanzek, J., Stevens, E. A., Williams, K. J., Scammacca, N., Vaughn, S., & Sargent, K. (2018). Current Evidence on the Effects of Intensive Early Reading Interventions. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 51(6), 612–624. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219418775110