Multiple Meanings of the Science of Reading

Executive Summary

The term Science of Reading has long been applied to reading programs and frameworks. It’s undergone a myriad of changes from its early use in the 1800s to describe pronunciation of primer words, to Kenneth Goodman and Frank Smith’s use to describe their hypotheses about whole language. Now it’s being used to describe reading programs that are “evidence-based.” While the term has a somewhat ambivalent history, it demonstrates a commitment to find an optimal reading program for each student.

While there are many different solutions posed by print and digital publishers, the basic Science of Reading implementation includes these key components: phonemic awareness, phonological awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and reading comprehension strategies, and the development of adequate content knowledge. Let’s Go Learn since its founding has focused on these foundational areas of instruction. Rather than promoting a one-size-fits-all solution, we lead with a granular, gap-driven, standards-aligned online diagnostic. Our system then uses the performance of each student to create a unique learning path of digital lessons that fill gaps and build on strengths.

Introduction

The term Science of Reading (SoR) is making a solid return as a post-COVID solution in a search to remedy recent NAEP reports of drastically low reading proficiency scores. This isn’t a new dilemma as low reading proficiency has plagued the educational system for years. Consider this quotation from an article by G. Reid Lyon and Vinita Chhabra: “The report of the most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) indicates that once again, 4th, 8th, and 12th grade reading scores are abysmally low, particularly among disadvantaged students….” Sound familiar? The article was written in 2004 (Lyon & Chhabra, 2004). In this current drive for the holy grail of reading instruction, teachers seek evidence-based practices for the diverse student population in US classrooms.

From Whole Language to the Simple View of Reading

The reading wars of the late 20th century pitted whole language reading instruction against phonics instruction. Whole language was accused of being untethered to research. Ironically the term Science of Reading was used by whole language advocates such as Kenneth Goodman and Frank Smith to describe their whole language framework which espoused that “we learn to read by making sense of what is on the page, and our knowledge of phonemic awareness, phonics, and the ability to read lists of words in isolation is the result of learning to read by reading” (Krashen, 2010).

Advocates of a more linear phonics path included Philip Gough and William Turner. They kicked off a dispute with whole language advocates, rejecting the notion that decoding is not central to reading comprehension. Rather they developed a theory called the Simple View of Reading. This theory proposes that decoding times language comprehension = reading comprehension.

To further explain the relationship of the two factors, Farrell et al discuss issues with decoding, background knowledge, and critical thinking: “A deficit in decoding is related to the student’s ability to read printed words accurately and rapidly. Any deficit in language comprehension is not specific to reading, but related to a knowledge domain or to higher order thinking skills such as reasoning, imagining or interpreting” (Farrell et al. 2019).

While many teachers have combined the two frameworks in their classroom instruction, some academics and politicians have continued to pit the concepts against one another. However, their insistence on a perfect solution that would meet the needs of all children has disregarded personal, language, and familial background, learning styles, socio-economics, personal interests, and neurodiversity.

Accelerate reading with actionable data!

From the National Reading Panel to the “new” Science of Reading

In 1997, Congress tasked the National Institute of Child Health and Development and the Department of Education “to assess the status of research based knowledge, including the effectiveness of various approaches to teach children to read.” To fulfill this request a National Reading Panel was formed. This panel formed subgroups to investigate Alphabetics, Fluency, Comprehension, Teacher Education, and Computer Technology. The effort resulted in the NRP report in 2000 (NRP, 2000). The report advised “explicit instruction in phonemic awareness, systematic phonics instruction, methods to improve fluency, and ways to enhance comprehension” (Reading Rocket, n.d.).

Following publishing of the NRP report, Reading First legislative requirements for Title 1 reading programs were developed and these required that programs be based on five key components: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and language comprehension skills and strategies. The legislation also set a school accountability goal that all students read by third grade.

In the same timeframe (early 2000s), Balanced Literacy programs were becoming popular. According to an article in the Hechinger Report (2020), Balanced Literacy was created as a solution to the whole language vs phonics reading wars and leveled reading. California was one of the first states to adopt the framework.

For more information about state and federal adoption of reading programs, check out our Education Reform article.

Practitioners of this ilk continue to insist on a one-size-fits-all pedagogy. In fact, David Kilpatrick is reported as saying:

“We teach reading in different ways; they [students] learn to read proficiently in only one way” (IMSE, 2021).

The National Institute of Literacy defines the Science of Reading approach as: “the direct teaching of a set of letter-sound relationships in a clearly defined sequence. The set includes the major sound/spelling relationships of both consonants and vowels” (National Institute of Literacy, 2006).

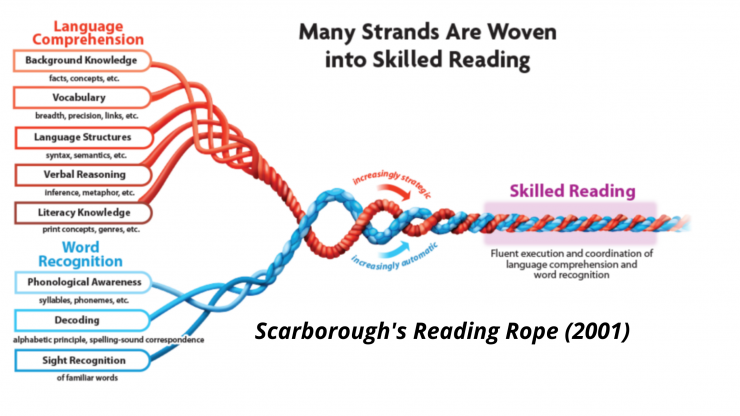

Image: Scarborough’s Rope, from North Carolina Department of Public Instruction

Not surprisingly many other voices and research studies continue to emerge. A popular framework and infographic is the Reading Rope concept. Staake defines the concept as follows: “Scarborough’s Rope contains two main sections: Word Recognition and Language Comprehension. Each of these comprises several smaller strands. Woven together, these strands become the rope that represents complete skilled reading” (Staake, 2021). Another approach is called Structured Literacy which focuses on the same five areas identified by the National Reading Panel report: Phonemic Awareness, Phonics, Fluency, Vocabulary, and Comprehension.

Tim Shanahan, in an article devised to quell the wars, advises that decisions on how to teach reading should follow the research rather than what is trending. He reminds readers that reading scores rose after the publishing of the National Reading Panel report in 2000. He goes on to say that during the last 20 years additional research on evidence-based reading practices have added to NRP advice. This research includes the use of “topics like writing and spelling to improve reading, text complexity, teaching reading comprehension within science and social studies, differentiation of instruction, quality of instruction, and text structure” (Shanahan, 2021).

The plethora of definitions for the term Science of Reading are no more obvious than in 2020 and 2021 when the International Literacy Association (ILA) responded to the dramatic increase in the use of the term. The organization ended up publishing two separate issues of Reading Research Quarterly (RRQ): “Unpacking the Science of Reading” and “Making Sense of the Science of Reading.” A statement by its Board should make the complexity of the Science of Reading concept clear: “Hence, it is essential that educators operate fluidly as reading is neither fixed nor standardized but variable….To attend to learners as they learn to read their words, their worlds, and those of others, educators need to be informed by the arts and sciences” (ILA, 2020).

By July 2022, 29 states and D.C. had passed a requirement that schools use evidence-based reading programs, commonly described as Science of Reading programs (Schwartz, 2022). However, given the wide variety of definitions of the Science of Reading, the requirement lacks teeth. Dianna Townsend, a reading researcher, writes that most researchers agree that phonics instruction and comprehension have a positive impact on a student’s reading ability. However, she adds: “We can teach children to read words and make meaning from texts in systematic ways that honor children’s identity, agency and culture” (Townshend, 2021). Perhaps it is time to revisit the recommendations of the NRP Panel of 2000. Nancy Bailey, an experienced special education teacher, in her post “Time for a new National Reading Panel to Study Reading Instruction” writes: “More children with disabilities are taught to read in school along with their peers in general education classrooms. What programs help them to learn to read? How can schools serve children with disabilities inclusively and effectively?” (Bailey, 2021).

Let’s Go Learn’s approach to reading instruction in LGL Edge Reading Series 3.0 integrates all five critical reading strands. Our LGL management system creates unique instructional paths for each student using their performance on our online diagnostic assessment. The end result is optimal learning accelerated by our innovative design — decreasing cognitive load while profoundly increasing engagement and motivation.

References

N. Bailey. (2021) Time for a New National Reading Panel to Study Reading Instruction. https://nancyebailey.com/2021/02/22/time-for-a-new-national-reading-panel-to-study-reading-instruction/

J. Barshay. (2020). Four things you need to know about the new reading wars. The Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/four-things-you-need-to-know-about-the-new-reading-wars/

Linda Farrell, Michael Hunter, Marcia Davidson, & Tina Osenga. (2019). The Simple View of Learning. Reading Rockets. https://www.readingrockets.org/article/simple-view-reading

R. Green. (2022). Evidence-based reading system outweighs state’s ‘balanced literacy’ approach. CalMatters. https://calmatters.org/commentary/2022/07/evidence-based-reading-system-outweighs-states-balanced-literacy-approach/

G. Reid Lyon & Vinita Chhabra. (2004). The science of reading research. ASCD. https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/the-science-of-reading-research

International Literacy Association Board Board. (2020). ILA launches landmark literacy research resource. https://www.literacyworldwide.org/docs/default-source/resource-documents/ila-board-statement-on-science-of-reading.pdf?sfvrsn=c762bc8e_8

Krashen, S. (2010). The Goodman/Smith Hypothesis, the Input Hypothesis, the Comprehension Hypothesis, and the (Even Stronger) Case for Free Voluntary Reading In: Defying Convention, Inventing the Future in Literacy Research and Practice: Essays in Tribute to Ken and Yetta Goodman. P. Anders (Ed.) New York: Routledge. http://www.sdkrashen.com/content/articles/many_hypothesis.pdf

National Institute for Literacy. (2006). Phonics Instruction: The basics. Reading Rockets. https://www.readingrockets.org/article/phonics-instruction-basics

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/pubs/nrp/Documents/report.pdf

K. Ordetx.(2021). What is the Science of Reading? Institute for Multi-Sensory Education. https://journal.imse.com/what-is-the-science-of-reading/

Reading Rocket. (n.d.). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read. https://www.readingrockets.org/research-by-topic/report-national-reading-panel-teaching-children-read#:~:text=The%20National%20Reading%20Panel’s%20analysis,and%20ways%20to%20enhance%20comprehension.

S. Schwartz. (2022). Which states have passed Science of Reading Laws? What’s In Them? EdWeek. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/which-states-have-passed-science-of-reading-laws-whats-in-them/2022/07

T. Shanahan. (2021). What is the Science of Reading? Reading Rockets. https://www.readingrockets.org/blogs/shanahan-literacy/what-is-science-reading-2021

J. Staake. (2021).What is Scarborough’s Rope and how does it explain teaching reading? WeAreTeachers. https://www.weareteachers.com/scarboroughs-rope/

D. Townsend. (2021). What is the “Science of Reading” and why does it matter? Nevada Today. https://www.unr.edu/nevada-today/news/2021/atp-science-of-reading

Leave A Comment